This article is the first chapter of Measuring the Mandates: Questioning the State’s Response to COVID-19. The full book is available here.

‘Democide means for governments what murder means for an individual under municipal law. It is the premeditated killing of a person in cold blood, or causing the death of a person through reckless and wanton disregard for their life.’

For many people, any initial feelings of cynicism regarding the dangers of COVID-19 dispersed in April of 2020, when excess mortality figures suddenly spiked around the world. England and Wales experienced nearly sixty thousand excess deaths during a three month period:

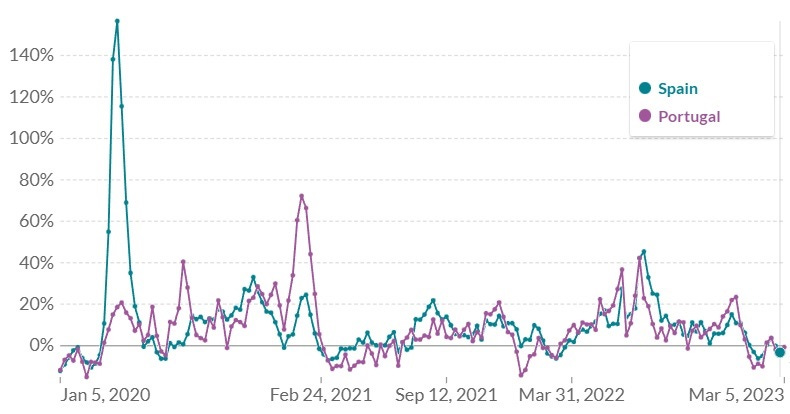

At the same time, excess mortality spiked across various European countries:

The identification of a novel coronavirus had been announced by the world’s media, then suddenly vast numbers of people started dying across multiple countries. Whilst correlation alone does not prove causation, surely the new virus must be the sole culprit for these deaths.

Two voices that were early in cautioning against an unguarded leap to such a conclusion were Dr. Claus Köhnlein and journalist Torsten Engelbrecht. Köhnlein and Engelbrecht are co-authors of the book Virus Mania, which critically examines the foundations and assumptions of virology. In an article published in October of 2020, they claimed that a comparison of excess mortality across countries actively disproved the viral hypothesis

They point out the striking contrast between neighbouring countries Spain and Portugal, where the former had 157% excess deaths, at the same time the latter’s peaked at 21%.

The same situation exists between Italy and Slovenia. During this initial period, Italian excess mortality peaked at 86%, whilst the Slovenian reached 11%. Italy’s excess was entirely concentrated in the North of the country, where Bergamo reached a 1,000% excess.

Germany also contrasts sharply with her high excess neighbours. Belgium's excess peaked at 105%, the Netherlands was 70, whilst France hit 61. Germany’s only reached 12% during this initial period.

A similar picture emerges in the United States. At the time New York was experiencing an over 130% increase in excess mortality (over 630% in some parts of New York City), neighbouring Vermont and nearby New Hampshire and Maine experienced little to no excess:

Köhnlein and Engelbrecht assert that:

‘A virus pandemic, which afflicts countries so differently, cannot actually exist, especially in today’s times.’

Is this true? Köhnlein and Engelbrecht provide no comparison to historical data to support their claim. Making such a comparison would also be difficult, due to the unprecedented steps taken to counteract COVID-19. We were truly living through unique times. The data is perhaps intriguing enough however, to at least look and see if any other factors could have been feeding into the excess mortality.

Out of concern for this situation, Claus Köhnlein submitted a letter to the German Ärzteblatt medical journal, stating:

‘In view of the fact that very different mortality rates are reported in different European countries, it is reasonable to assume that a differently aggressive therapy could be responsible for this.’

Köhnlein and Engelbrecht focus on drug trials, stating that:

‘This is why there can only be a non-viral explanation for this temporary massive excess mortality. And there is solid evidence that the massive and high-dose administration of highly toxic drugs plays the decisive role—drugs that have been used in worldwide trials and also beyond these trials, costing the lives of tens of thousands of test persons. In the course of time the “patient supply” dried up which explains the rapid drop in the curves creating these “prongs.”’

In opposition to the viral hypothesis, this position has become known as the iatrogenic (medically induced) hypothesis of COVID-19.

In a paper supporting the iatrogenic hypothesis, Dr. Denis Rancourt draws attention to comments made by World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, on March 11th 2020, when declaring a pandemic:

‘I remind all countries that we are calling on you to activate and scale up your emergency response mechanisms; communicate with your people about the risks and how they can protect themselves – this is everybody’s business; find, isolate, test and treat every case and trace every contact; ready your hospitals; protect and train your health workers.’ [emphasis added]

Tedros Adhanom’s advice is consistent with WHO pandemic preparedness documents.

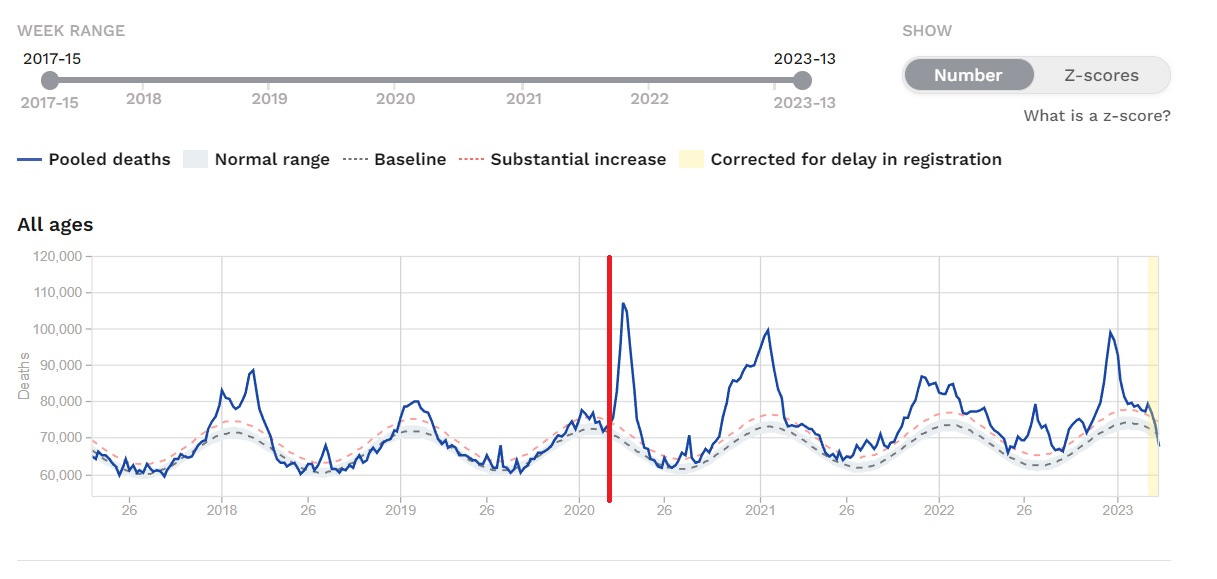

The COVID-19 virus is reckoned to have been spreading over the world for months at this point, yet there was no sign of excess mortality anywhere except possibly China. Immediately after the WHO declares a pandemic and makes reference to making hospitals ready, the death rate dramatically spikes in various European countries, US States and Canadian provinces. These spikes are unprecedented in both their scale and the fact that they take place outside of the usual flu season. They occur simultaneously in geographic areas separated by thousands of miles, yet not necessarily in neighbouring countries or even provinces.

Various explanations are offered as to how the virus could spread without noticeably affecting mortality rates, then suddenly transform itself into the worst killer in a century. None of these explanations can account for the WHO’s seeming ability to predict the onset. Dr. Rancourt proposes that it is far more likely that the excess mortality was due to the implementation of pandemic preparedness across the regions that suffered with it.

This is the excess mortality for all of Europe, with a red line added to indicate the date of the WHO announcement.

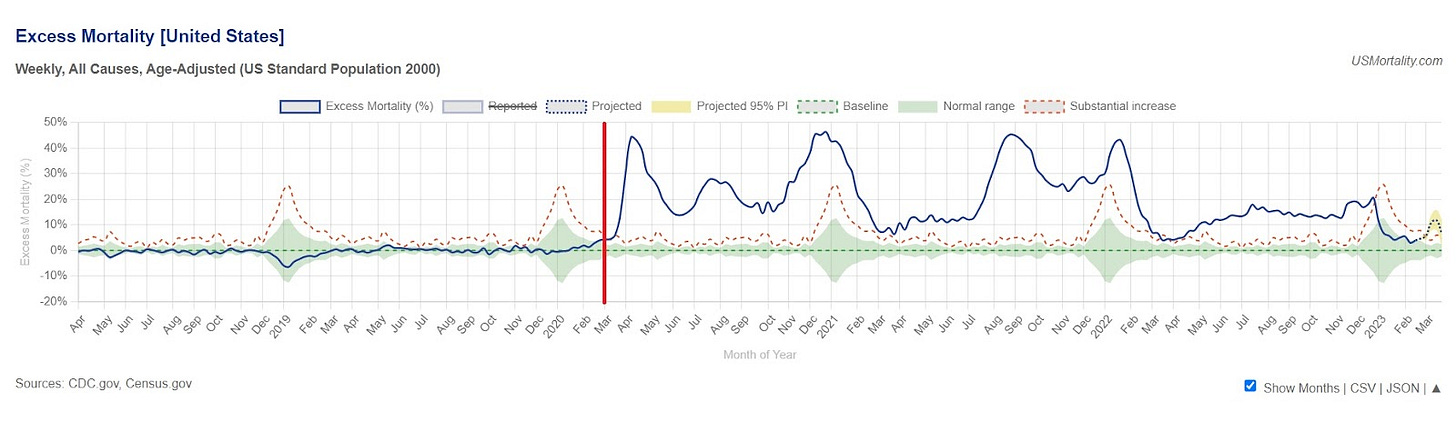

And this is the United States:

Although COVID-19 was apparently circulating, there was simply no excess prior to this point outside of the annual flu season. Europe is more similar to the United States than France is to Germany, Spain to Portugal, or New York to Vermont.

We will now examine what the various implications of readying hospitals were for excess mortality.

Denial of access to hospitals and other medical services

In October of 2020 Amnesty International published a report titled As if Expendable: The UK Government’s Failure to Protect Older People in Care Homes During the COVID-19 Pandemic. It makes for a truly harrowing read. Amongst many issues, the report highlights elderly people being refused medical care after the declaration of a pandemic:

‘Amnesty International has received multiple reports of care home residents’ right to NHS services, including access to general medical services (GMS) and hospital admission, being denied during the pandemic, violating their right to health and potentially their right to life, as well as their right to non-discrimination. Care homes managers have pointed out that such reluctance or refusal to admit older care home residents to hospital could not be explained by need, as hospital bed capacity was never reached.’

‘The problem was widely reported early on in the pandemic, and was seemingly exacerbated by guidelines published by NHS England on its website on 10 April advising that some care home residents “should not ordinarily be conveyed to hospital unless authorised by a senior colleague.” The guidelines caused a controversy and were withdrawn a few days later but the damage lingered.’

‘Official figures show admissions to hospital for care home residents decreased substantially during the pandemic, with 11,800 fewer admissions during March and April compared to previous years.’

‘The son of one care home resident who passed away in Cumbria said that sending his father to hospital had not even been considered:

“From day one, the care home was categoric it was probably COVID and he would die of it and he would not be taken to hospital. He only had a cough at that stage. He was only 76 and was in great shape physically. He loved to go out and it would not have been a problem for him to go to hospital. The care home called me and said he had symptoms, a bit of a cough and that doctor had assessed him over mobile phone and he would not be taken to hospital. Then I spoke to the GP later that day and said he would not be taken to hospital but would be given morphine if in pain. Later he collapsed on the floor in the bathroom and the care home called the paramedic who established that he had no injury and put him back to bed and told the carers not to call them back for any Covid-related symptoms because they would not return. He died a week later.

“He was never tested. No doctor ever came to the care home. The GP assessed him over the phone. In an identical situation for someone living at home instead of in a care home, the advice was “go to hospital”. The death certificate says pneumonia and COVID, but pneumonia was never mentioned to us.”’

‘Reduced possibility to send care homes residents to hospital compounded another long-standing issue, that of care homes residents’ limited access to GPs. Obtaining access to GPs got markedly more challenging during the pandemic, as GPs throughout the country switched to phone/online consultations and stopped visiting care homes. NHS England advised GPs to begin the roll out of remote consultations on 17 March 2020, prioritising vulnerable groups but limiting face-to-face consultation to only “when absolutely necessary.” However, Amnesty International received multiple reports from care homes managers and staff and relatives of care home residents throughout the country of doctors refusing to enter care homes and only being available for consultations by phone or via video calls, no matter what the residents’ symptoms were and even in regard to end-of-life support.’

‘The daughter of a care home resident who died in Liverpool described the lack of medical care her father experienced:

“In the file it says that dad complained of chest pain on 28 March and asked to see a doctor but there was no follow up in the file … In the file it also says that dad had fallen on morning of 1 May and banged his head and had a swelling. I was never told and there is no record of a doctor being called for this. On 1 May a carer told me they had rang the doctor but the doctor was not going in [to the care home] and had prescribed antibiotic and end of life drugs. Then I spoke to the GP and he said he suspected COVID or chest infection and that I should go see him. Dad died on 2 May and a staff member told me she was there when dad died and he was gasping for breath and holding his chest.”’

It is self-evident that the withdrawal of medical care will cause excess deaths. It is also worthy of note that a GP was willing to prescribe end-of-life drugs over the telephone.

Misuse of ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ (DNAR) forms

Amnesty quote Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights from September of 2020 as saying:

‘The blanket imposition of DNACPR notices without proper patient involvement is unlawful. The evidence suggests that the use of them in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic has been widespread.’

And go on to report that:

‘Care home managers reported to Amnesty International and to media cases of local GP surgeries or Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) requesting them to insert DNAR forms into the files of residents as a blanket approach.

‘Asked about any blanket approaches to DNARs, one care home owner in the north of England told Amnesty International, “We had a letter to that effect from the practice. I refused to sign it and handle it like that.” Another reported that they were asked to insert DNAR forms into a number of residents’ files. A family from Lancashire told Amnesty International that their relatives had been asked to sign a DNAR form without having understood what it meant.

‘“The nurse from the GP surgery rang me up to say they decided mum is DNR. I asked why and she said “we did this across the home”, and I said “no, this should be done on individual cases and I don’t agree to it”. So I had it taken off … She also said that they would not take mum to hospital and again I said that is something that would have to be decided if and when need arose on the basis of the situation at the time. They had asked mum about the DNR and she had agreed to it but then I spoke to mum and she had not really understood the issue.”’’

Discharge of patients from hospitals into care homes

Amnesty reports that:

‘On 17 March 2020 NHS England announced the decision to urgently discharge patients, including those who were infected or who may have been infected with COVID-19, from hospitals into care homes and the community. This was among the most crucial decisions that adversely affected care homes across the country.’

‘According to the National Audit Office, this policy led to 25,000 people being sent untested from hospitals into care homes between 17 March and 25 April, putting at risk the health and indeed the lives of care home residents. The DHSC did not collect data on the extent to which care homes successfully isolated residents with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 and did not require local authorities to collect data either.’

‘The discharge of thousands of patients from hospitals to care homes in the days following 17 March was extremely rushed, leaving little or no time for consultations and assessments. “We had 500-600 empty beds and nobody coming into A & E so there really was no need for such rushed discharges,” a member of a discharge team at a hospital in the south of England told Amnesty International. A care home manager recalled: “Families learned their relatives came to care homes on the spot. There was no time for them to discuss with hospitals or with us. Families had no chance to choose which care home, to visit the place, to meet us. People’s teeth and glasses went missing in the rush.”’

In addition to infection risk, this also represents the denial of (presumably necessary) hospital care to thousands of elderly people—an action guaranteed to raise the death rate.

Increased workload, reduced staffing levels and removal of oversight for care homes

Compounding the medical problems, Amnesty’s report identified how COVID regulations reduced the number of staff, whilst increasing the workload of the remaining ones:

‘According to the National Audit Office, workforce shortage in the care sector pre-pandemic was already estimated at 122,000 and staff absence increased significantly during the pandemic, with absence rates in care homes between mid-April and mid-May 10% on average, and considerably higher in certain care homes or areas. The lack of testing exacerbated this problem as it was impossible to know if some of those self-isolating were COVID-19 free and could in fact work. Staff shortages in turn impacted the ability of care homes to adequately manage infections and the quality of care they were able to provide for residents, both those infected with COVID-19 and others. This was exacerbated by a situation where care home staff had to perform a number of additional tasks—from assisting residents to communicate with their relatives who could no longer visit them, to enforcing social distancing among residents unable to understand the requirement because of dementia, to cutting residents’ toenails because chiropodists stopped visiting care homes, to interpreting and communicating residents’ symptoms to GPs who were no longer visiting care homes, etc.’

This coincided with the removal of oversight from care homes, with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) suspending inspections and family members banned from visiting:

‘Beginning on 16 March 2020, the CQC announced that it would be ceasing its routine inspections of care homes, leaving open only the possibility of visits “in a very small number of cases when we have concerns of harm, such as allegations of abuse.” In its announcement, CQC said its primary objective was supporting providers “to keep people safe” and so there would be a “shift towards other, remote methods to give assurance of safety and quality of care.” Notably, this decision meant that at a time when older people in care homes were most vulnerable—because of the virus and because those who usually advocated on their behalf could no longer visit them—the regulator was largely absent.

‘The lack of official visits occurred at the same time as a ban on other visits—from family and friends, as well chiropodists, hairdressers, nurses, and others—which were normally an important source of information for the CQC. Expert noted that “[CQC] have been unable to rely on the ‘eyes and ears’ of visitors to raise the alarm and care workers have been frightened to speak out.”’

In other countries

Reports from the various countries experiencing high excess mortality at this time tell a similar tale. They were all engaged in isolating their elderly population and denying them medical care. In a report into the care home disaster in Sweden, the BBC quote a nurse as saying:

‘They told us that we shouldn't send anyone to the hospital, even if they may be 65 and have many years to live. We were told not to send them in.’

In Spain, soldiers were brought into care homes and found residents dead in their beds, abandoned. In French homes, Reuters reported that ‘bodies have been left decomposing in bedrooms’. In Canada, the C2C Journal reported that:

‘Quebec’s Health Ministry issued a directive on March 19 – barely a week after the global pandemic had been declared – instructing nursing homes not to send residents to hospitals unless in exceptional circumstances. Conversely, hospital patients who were not in critical condition were to be either sent home or transferred to care homes. This practice was adopted in multiple jurisdictions: Quebec, Ontario, several U.S. States including New York and New Jersey, and in England.’

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s order to nursing homes to admit COVID-19 patients was found by the State Bar Association to have increased the death toll among residents. New York also made extensive use of ventilators, which are estimated to have killed tens of thousands of Americans unnecessarily.

End-of-life drugs

In 2020, British journalist Jacqui Deevoy began documenting stories of people who contended their family members had been effectively murdered by the NHS, through being involuntarily put on ‘end-of-life pathways’. This would be unbelievable, had it not already happened within the past decade, with the infamous Liverpool Care Pathway being phased out as recently as 2014.

Ms. Deevoy placed particular emphasis on the sedative drug, midazolam. She documented family members’ accounts in her film, A Good Death? The documentary is a harrowing yet informative watch, where family members back their observations with data regarding the doses of midazolam being administered. They highlight a paradoxical effect, where the drugs given to treat an ailment actually produce the symptoms of that ailment, leading to the delivery of more drugs. The following quotations illustrate the families’ experiences:

‘Because they said “you can’t feed your wife”, as I was feeding her I was looking out the door. She said, “what do you keep looking at?” I said “I’m making sure the nurses aren’t coming in.”’

‘I’ve since found out that he was starved as well. His routine diet was discontinued three days before his death, with no water either.’

‘I think what happened was, because they neglected her, and they gave her a high dose of midazolam and morphine, because it is a respiratory suppressor, and they dehydrated her for such a long time, those drugs compounded and they were magnified in terms of potency, because she just couldn’t get the oxygen, she just suffocated.’

‘The last thing she said to me was: “get me out of this hospital, they’re trying to kill me.”’

‘What does it say on his death certificate that he died of?’

‘COVID-19 pneumonia'

‘And what do you think he died of?’

‘The midazolam.’

‘He was killed?’

‘Yes’

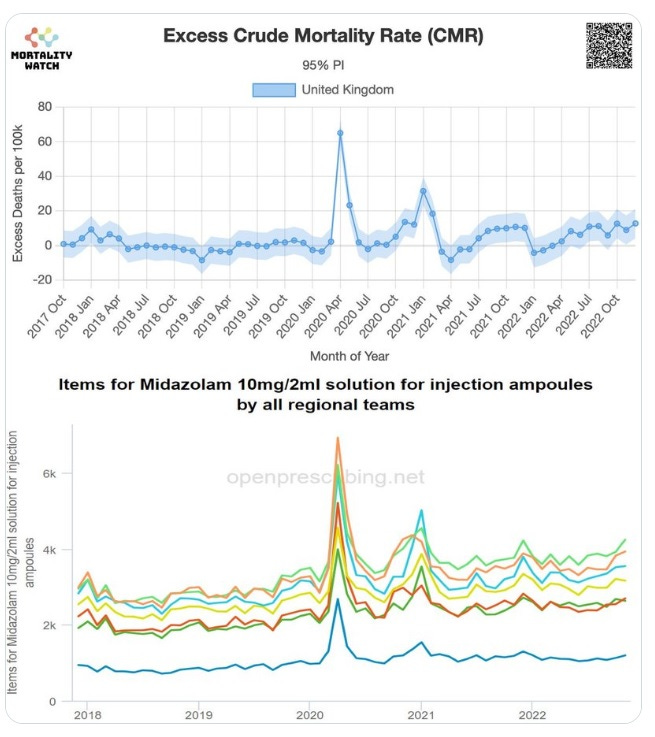

As we’ll see in a moment, midazolam use spiked in April of 2020. Was this because so many people were dying of COVID, or were people dying because of the increased use of a respiratory suppressant drug?

In a presentation titled Euthanasia in the Pandemic? Dr. John Campbell addressed this question by referring to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) COVID treatment guidelines, published on the 3rd of April 2020. The key line that jumps out in the Managing Breathlessness section is:

‘Sedation and opioid use should not be withheld because of an inappropriate fear of causing respiratory depression.’

Dr. Campbell questions whether a fundamental mistake was made in transferring the guidelines for incurable conditions onto a potentially completely recoverable one. He points out that if an opioid and a benzodiazepine (such as morphine and midazolam, respectively) are given together, they will have the effect of stopping the recipient breathing. He states that:

‘Opioids and benzodiazepines will depress respiration. A lot of these people were breathless anyway, they had acute respiratory distress syndrome. If you have a lot of fluid in your alveoli you'll breathe more quickly to try and compensate and that can get enough oxygen into your body to mean that you survived the acute episode. But if you give these drugs, and you get respiratory depression, I don't think you need me to spell out the consequences of that. Not enough oxygen, tissue hypoxia, and death would be the result.’

Dr. Campbell goes on to say:

‘So they said “consider an opioid and a benzodiazepine like midazolam combination for patients with COVID-19 who are at the end-of-life.” But how many patients with COVID-19 would be at the end-of-life, unless they had some intractable condition at the same time? And how do you know if they're at the end-of-life? I've looked after hundreds of patients where I’ve thought “good grief they're not very well”, but the vast majority of them survive with an infectious condition. You can't really tell whether it's the end-of-life or not.’

And:

‘Even with moderate breathlessness people might have looked ill but had a virus that their immune system could have overcome. They could have recovered, but could well have been given these medications that resulted in suppressing their breathing.’

Serious concerns over the NICE guidelines were raised as early as the 20th of April 2020, in a letter to the British Medical Journal signed by two professors and nine doctors. They warned:

‘The combination of opioid, benzodiazepine and/or neuroleptic is used in specialist palliative care settings for symptom control and for ‘palliative sedation’ to reduce agitation at the end of life. It takes great skill and experience to use palliative sedation proportionately so that extreme physical and existential distress are palliated, but death is not primarily accelerated. NG163 states: “Sedation and opioid use should not be withheld because of a fear of causing respiratory depression.” If COVID-19 infection were uniformly fatal, this would be an acceptable statement. But for people not previously known to be at the end of life, there is potential risk of unintended serious harm, if these medications are used incorrectly and without the benefit of specialist palliative care advice.

‘Another concern is that the recommended doses for morphine and midazolam are sometimes higher than current guidelines state for non-specialist use; and moreover there are inconsistencies between the maximum doses recommended by the oral or subcutaneous routes.’

Vastly increased use of midazolam is not only apparent, it corresponds with the increase in excess mortality seen in 2020.

Dr. Campbell goes on to demonstrate a similar spike in prescriptions for the drugs levomepromazine and haloperidol, the latter of which is not approved for use in older adults due to ‘risk of death’.

There is also evidence for increased midazolam use in Italy and Sweden. Israel National News reported comments from Swedish Professor of Geriatric Medicine, Yngve Gustafson:

‘“Living in a nursing home is not a diagnosis. By itself it can never be a medical basis for deciding whether to live or die”. Gustafson said that nutrient drip treatment, blood clot prevention, oxygen and bacterial pneumonia treatment with antibiotics would help the elderly. “Instead, giving morphine and midazolam regularly to elderly people with lung infection is active euthanasia, if not something worse. We gave up the elderly who could have had a chance of survival”.’

Decrease in antibiotics prescriptions

In 2008 none other than Dr. Anthony Fauci himself co-authored a paper on postmortem studies of victims of the pandemic of 1918. The paper found that:

‘People who died of influenza during 1918–1919 uniformly exhibited severe changes indicative of bacterial pneumonia. Bacteriologic and histopathologic results from published autopsy series clearly and consistently implicated secondary bacterial pneumonia caused by common upper respiratory-tract bacteria in most influenza fatalities.’

And concluded that:

‘The majority of deaths in the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic likely resulted directly from secondary bacterial pneumonia caused by common upper respiratory-tract bacteria. Less substantial data from the subsequent 1957 and 1968 pandemics are consistent with these findings. If severe pandemic influenza is largely a problem of viral-bacterial copathogenesis, pandemic planning needs to go beyond addressing the viral cause alone (e.g., influenza vaccines and antiviral drugs). Prevention, diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of secondary bacterial pneumonia, as well as stockpiling of antibiotics and bacterial vaccines, should also be high priorities for pandemic planning.’

Given this, in combination with Dr. Fauci’s prominent role during the pandemic, it is surprising that we haven't heard more about the dangers of secondary bacterial infections over the past three years. What role have they played in COVID-19 deaths?

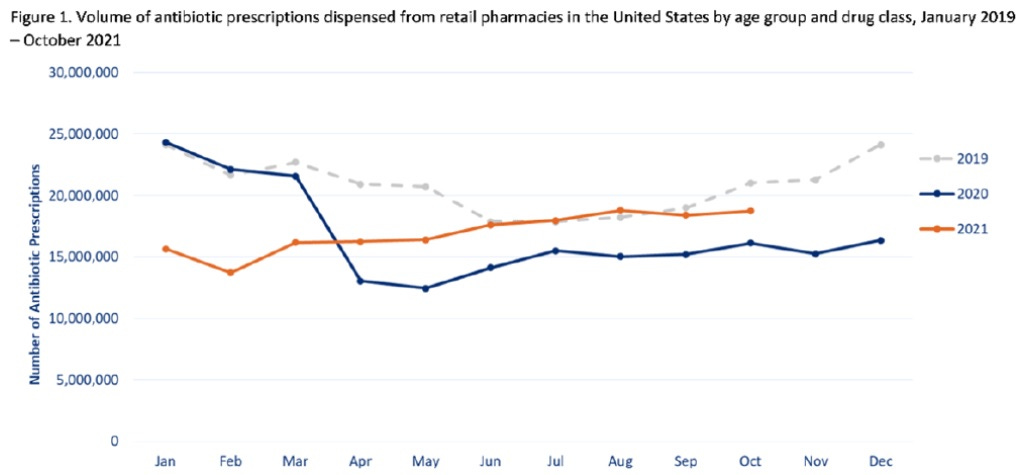

In actual fact it is no secret that prescriptions for antibiotics fell dramatically through the COVID era, once again in a manner that correlated with rising excess mortality:

Antibiotic rates in March of 2020 are comparable with the previous two years. Prescription rates decrease in April, then remain low until 2022. The previous winter spike is simply not present in January of 2021, at exactly the time an unusual spike arises in excess mortality.

A similar situation is observable in the USA:

This data led Dr. Denis Rancourt to propose:

‘It is not unreasonable to ask whether the logic has not been inverted: Is COVID-19-assignment an incorrect cause-assignment for what is in fact bacterial pneumonia?’

‘If COVID-19 is largely misdiagnosed bacterial pneumonia (using a faulty PCR test: Borger et al., 2021; or not using any laboratory test), or if co-infection with bacterial pneumonia is not appropriately recognized (Ginsburg and Klugman, 2020), or if bacterial pneumonia itself goes otherwise untreated, while antibiotics (and Ivermectin) are withdrawn, in circumstances where large populations of vulnerable and susceptible residents have suppressed immune systems from chronic psychological stress induced by large-scale socio-economic disruption, then the state has recreated the conditions that produced the horrendous bacterial pneumonia epidemic of 1918 (Morens et al., 2008) (Chien et al., 2009) (Sheng et al., 2011), in COVID-era USA.’

Conclusion

The aim of this chapter has not been to demonstrate what caused the increase in excess mortality over the past several years. Instead, it has been to identify that multiple factors have been at play, and it is not easy (perhaps impossible) to point to one of them as causal.

Perhaps Claus Köhnlein and Torsten Engelbrecht will ultimately be proven correct, that all excess deaths were iatrogenic. Maybe Denis Rancourt’s view that a virus was involved, but not necessarily a novel one, will win out. Maybe the deaths are a split between a novel coronavirus and iatrogenic factors. It is certainly far beyond the scope of this document to come down on any side of a line.

What is well within scope, is to propose that this question—the question of what caused the excess deaths—is undoubtedly one of the most important in the world right now. Without answering it, societies around the globe will be doomed to repeat the devastating mistakes of the COVID era.

This article is the first chapter of Measuring the Mandates: Questioning the State’s Response to COVID-19. The full book is available here.

If the virus had been spreading for months before the lockdowns (which my research proves is an almost-certainty), we would have seen some of these massive "all-cause" death spikes in numerous countries, states or cities weeks or months before these spikes.

The official narrative is that we actually had "late spread" (in the Spring of 2020), which caused the sudden explosion in deaths in multiple locations all at essentially the same time. I think most thinking people now agree this (very contagious) virus was spreading by November 2019 (if not October or September). But the deaths didn't start happening until mid to late March 2020? Coincidentally, right after all the medical protocols changed.

The average time from infection to death is about 17 to 19 days. So if many people were getting sick in, say, December 2019 - the deaths would have started showing up in late December or maybe early January. But as these charts show, there was no noticeable spike in deaths.

This was a form of government/bureaucrat caused homicide ... on a massive scale.

The only medical homicide in history that was bigger was a year later ... when the same people and governments mandated the Covid shots.

That is, the government killed massive numbers of people ... in 2 different ways. And this doesn't include the "collateral" deaths from the lockdowns. So I guess that would be the mass death trifecta.

Imagine the uproar if a parallel program to, let's imagine, wipe out all the k-9s on the planet by some modified K-9 viral scenario. There would be an ARMY of civilians ready to KILL and demanding answers before the lynching began.

But here, we have a FAR more serious condition in the laps of the inhabitants of planet earth, and there is not a single plowshare having been formed into a sword.

This is a peculiar thing, from my point of view!

R.